Anchorite Writing

or (A Bouncy Ball, Mountains, and a solution)

by Aida Ramirez, Eli Petzold, and Gabriel Chalfin-Piney

The following is a 72 hour writing project conceived as an introduction, in which I brought together two friends-loves-collaborators to meet for the first time, the meeting doubling in the creation of a writing project. We each had a private exchange and then I proposed this project:

My proposal for us three - to come up with 1-4 questions or writing prompts for the other two people to answer related to some ideas we have been having lately (maybe find commonalities).

The prompts are visible at the bottom of this writing project in the form of a key. Each numbered prompt corresponds to a response, available below. The numbers indicate the authorship of each of the prompt responders, but the authorship of the prompts have remained anonymous. I invite you to spend time with this key after you have finished moving through this project. Bookmark this page. Read one as a daily reflection when you wake up, or when you are on the toilet, take as long as you need. These are here for you. Thank you for your time. I love you.

* Gabriel

1

have you ever watched a moth fly?

seen em loop up and round

an skitter down

to fall right outa the sky

but only a little before they catchem selves again?

well they fly an they fall an they loop round an skitter

they have a hard time goin straight

cause the sunlights like glitter

and i sure would like to fly right into the glitter too

but i think it’s just somethin that moths do

2

A select, somewhat wrong timeline of the prehistory and history of the city of Klagenfurt, in Carinthia, in Austria, in Europe, &c. &c. &c.

Throughout the Upper Pleistocene: small oscillations in the earth’s axial tilt and orbit trigger cycles of global cooling and warming, in turn triggering cyclical migrations of Europe’s Coelodonta antiquitatis population from the lowlands to the highlands to the lowlands, &c.

Sometime in the Upper Pleistocene: a Coelodonta antiquitatis specimen dies in Carinthia

40,000-30,000 BP: the range of Homo sapiens expands into Europe; the fossil record indicates Homo sapiens hunt Coelodonta antiquitatis for meat, fur, and tools; populations of the latter, however, appear to remain stable

Throughout the Upper Paleolithic: Europe’s early humans depict the woolly rhinoceros on cave walls, in clay figurines, &c.

15,000-13,000 BP: Coelodonta antiquitatis vanish from Europe; although a sudden warming period appears the primary culprit, the influx of Homo sapiens and its expanding range in the lowlands of Europe cannot be ruled out as an auxiliary factor in inhibiting Coelodonta antiquitatis from recovering its range, in driving it to extinction

4000-2000 BCE: the earliest known inhabitants of the present-day Klagenfurt metro area—members of the Urnfield and Halstatt cultures—settle the region’s hills and moors; the lowlands of today’s city center remain marshy, prone to flooding from the nearby river Glan, and, therefore, unsettled

Once upon a time: a Lindwurm lives in the shallows along the river Glan, feeds on livestock and locals lost or straying in the swamplands; but the dragon’s environmental terror poses the gravest existential threat to the idea maybe someday of a city down there, washing away river crossings and river crossers, drowning travelers from near and far; the Lindwurm, it seems, wishes to preserve its watery place, to resist the ambitions of men who would change the form, function, and name of the place it calls home; if they’ll call it a ford, let them call it a bad one

1190s CE: the earliest known attestation of Klagenfurt’s name appears in a document about ducal tolls; the Forum of Chlagenvurth, as it is called, refers to a small market that had been established at an important trading crossroads in the lowlands along the river Glan; the name quite literally means “Ford of Lament” but that’s an accident, or a series of glitches in history, in onomastics, in linguistics; one theory starts with a wet Latinate toponym—maybe “Place by the Water”—warping beyond recognition into a form resembling an Old Slovene word meaning “lamentation;” to make a long story short—if only I could; to make a long story short—some semantic and phonetic cargo appears to have washed away during perilous crossings between late Latin, early Romance, Old Slovene, Middle German; folk etymologies filled the gaps in the fossil record, until these reconstructions supplanted any trace of the original that might have remained, became fossilized in their own right

Once upon a time, again: the Duke promises a reward for any would-be dragon-slayer; an enterprising troop of brave fighters materializes; dangling a bull on a fishhook from a tall tower by the swamp, they lure the Lindwurm and manage to slay it

1246: the city of Klagenfurt is reestablished in a more stable location, less prone to flooding

1287: the city’s earliest known coat of arms depicts a dragon in front of a tower

1330: the Lindwurm’s skull is discovered in a nearby quarry; displayed in the Klagenfurt’s town hall, it becomes a point of civic pride

1590: commissioned by the city, sculptor Ulrich Vogelsang completes a 6-ton statue of the Lindwurm, modeled after and extrapolated from the skull; three hundred youths, robed in white, transport the sculpture to Neue Platz, in the city center; it was always supposed to be a fountain, but that takes another forty years; it was always supposed to be a reconstruction of a long-dead creature based on material evidence, but it takes another three or so centuries for us to recognize this as the earliest known, clear example of paleoart (not to be confused with Paleolithic art.

1612: in the earliest known printed history of Carinthia, humanist scholar Hieronymus Megiserus, seeking a less folksy etymology of Klagenfurt’s name, floats the notion that it has something to do with the river Glanfurt, which flows into the Glan; it’s certainly wrong; those sounds don’t change like that; there are laws about these thing.

1840: paleontologist Franz Unger visits Klagenfurt and floats the notion that the Lindwurm skull is, in fact, the cranium of a woolly rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis)

3

When I was one I was tall and reached up to the blue, blue in ice trays, blue in tears, blue in the things I thought I should fear.

When I was two I was with you all, sloping, hurdling, ready to fall.

When I was three I learned how to speak. I saw how my body was just two mountains tucked together, overlooking a brook, hearing people row by, hearing a train surround my calves, lurching down my metal toenails. When I was four I saw I would have to move my body, which I did not move for many lives, I grew old, four was just a number, it had no signifier, no value. When I was five I believed I could fly, I could move up and out, detach from the form of the mountain and the lock of the earth. When I was six I would lay my head on the crease of your shoulder, and the stream would run between my thighs covered in someone’s dropped ice cream. When I was seven I thought I’d never get any older, I could fit in between a trap, push the metal up and over, leaving space by the wooden bed, with knots of eyes. When I was eight I rubbed my eyes and filament fell down to the mud, I crawled out, smaller and prouder, dangerous in my youth. When I was eight someone told me I was toxic, they said that my hair made them itch, they said they wouldn’t touch me alive or dead. When I was nine my dense barbed hairs began to molt. They would blow in the wind and I would feel lighter and more handsome. When I was ten my human friends again would mock me, they would say that severe problems were happening because of my new haircuts. They said that they were suffering respiratory ailments because of my behavior “just being near me” made them develop dense posion-ivy-like-rashes all over their bodies. When I was eleven people called me an infestation, they told me that their body rashes had shifted locations, morphed, shrunk and expanded. When I was twelve I became the rash of their nightmares, I embraced the villainy they had thrust upon me. Each night I would dot around their body, the rash itself would take on my form, they would know how it felt to be old and young, here and nowhere. On my thirteenth birthday I will complete my obligation of reading a Haftarah portion on the occasion of my Bat Mitzvah.

With Love,

A 164,000 year Double-Summit Mountain that becomes a Brown-tailed moth caterpillar by Osmosis

4

There’s a reoccurring daydream to run away. It’s always there and it’s like grazing a hot iron when the impulse strikes. I withdraw. I pull back. From things, tasks, people, and whatever there is to pull back from, I find a way to pull back from it. And when I get there, to the place I withdraw to, I only find myself. And unfortunately, I find myself Boring.

I make this mistake, every time, without fail, to always wish for space from things and tasks and people. And then as soon as I have it. I hate having it. In the Space is Boredom. The idea of space will always be nice but once I get a minute to look at myself in the mirror (because I’m out of everything else to occupy myself with doing) I am finally able to have an honest conversation with myself. And once I’m looking in the mirror I have to say–

take a deep breath and take a step closer once more.

5

Below are the opening lines of The Wanderer, an Old English elegy that meditates on solitude & exile in the wake of catastrophe (the death of a dear friend, the violent disintegration of a community). The poem probes the deep pangs of isolation & dislocation, but it also offers an image of the ideal exile—their demeanor & their duties despite the suffering.

Oft him anhaga are gebideð,

metudes miltse, þeah þe he modcearig

geond lagulade longe sceolde

hreran mid hondum hrimcealde sæ

wadan wræclastas. Wyrd bið ful aræd!

Swa cwæð eardstapa, earfeþa gemyndig,

wraþra wælsleahta, winemæga hryre:

Oft ic sceolde ana uhtna gehwylce

mine ceare cwiþan. Nis nu cwicra nan

þe ic him modsefan minne durre

sweotule asecgan. Ic to soþe wat

þæt biþ in eorle indryhten þeaw,

þæt he his ferðlocan fæste binde,

healde his hordcofan, hycge swa he wille.

Ne mæg werig mod wyrde wiðstondan,

ne se hreo hyge helpe gefremman.

Often him and I are giving

Depths of myth, here there he models caring

Gone grown languid long schlong

There in mid hunger hrimcealde sæ

Where in wrists clad God-given beautiful air!

So cast upon your table, all that you’ve given back

Wrap wild a sheathe of shadow, wine-made and heaving:

Or if you will hold anew another lover

Mine ceases to live. Nor tears nor modesty, my din quickens and ends.

For if you are that faint noise in the ear gliding through,

That he has betrothed and fastly bound, he in his grandest wears,

How else would he show. Nore me within modification God-given with intention, standing not seeing here in or here out helping us all to be filled.

6

you’re probably gonna need a bike– or at least that’s how i do it:

start by leaving home out the back door, head north east and go downhill about 1 ½ -ish miles. it’s usually okay to coast but be ready to swerve in case people pull out of their driveways too fast. take a sharp left and lean into the curve– keep right to stay on the road. turn left and turn right again to stay on the road. slight left onto Main St but only slight– don’t pass up the coffee. GO IN AND GET THE SPINACH CROISSANT WITH YOUR COFFEE OR ELSE YOU’LL GET A TUMMY ACHE. head west about a ½ mile and turn left. go down the first alley on the left. the building is unmarked but just ring the bell and someone will let you in. FEEL FREE TO WORK OR NOT. IT’S WHATEVER. when you leave, head right out the alley again and another right back toward the street. Turn left onto the street and after a little over a ¼ mile, turn right. WHEN YOU WALK IN, MAKE SMALL TALK WITH THAT ONE GUY WHO ALWAYS REMEMBERS YOUR NAME BUT YOU DON’T REMEMBER HIS. CHANCES ARE HE WILL RECOMMEND A BOTTLE OF WINE AND CHANCES ARE IT WILL BE VERY GOOD. bottle acquired, head north toward the water. you’ll have to do a quick left right left kind of situation in ¼ mile bursts but you’ll find the water eventually. I ALWAYS SIT FOR A BIT BUT YOU DON’T HAVE TO IF YOU DON’T WANT TO.

7

I will try, I’m gonna try, I’ll try, I’m trying, I try, I will have tried, I was trying, I’ve been trying, I’ve tried, I tried

(You would try too if it happened to you)

8

On March 23rd 2010 my grandmother Audrey sent me a message on facebook:

“Hi honey,

Just wanted to say again, what "nachas I schepped" from you this weekend. It will be a memory I will never forget! You have a wonderous life ahead of you, I envy you! Make the most of it, so you don’t have any regrets in your dotage.

Try to enjoy every day, and appreciate Randi and Hugh, and how much they love you, even when they bug the shit out of you! Good luck in whatever the future holds, and remember,

I love you always and forever,

Armoire”

I realized at some point—after this exchange—I unfriended my grandmother on facebook. She died 77 days later on June 8th. June 8th also happened to be my last day of high school. June 8th also happened to be my father’s birthday. I used to regret my behavior surrounding this period of her getting sick, passing, and the months that followed. I had no tools to face grief, I had no tools to detach, to offer love up to my family or self.

I vividly remember June 8th 2010. We were sitting in the living room at The Barn, our home, 25% of the space that made up The Barn, inhabited by other Quaker teachers, or teachers to the Quakers, or teachers with the Quakers, or people who just found out about the Quakers. We were sitting at the kitchen table, near the fireplace, near the couch, near the tv, near that tall magnificent wooden set of drawers. We had roasted braised duck paired with goat cheese, arugula and beet salad—celebrating my fathers birthday. Have I fed you this? We all walked over to The Computer Room as one of my parents answered the phone. “She has passed.” Almost immediately after getting the news of my grandmother’s death, a young deer banged it’s head on the window in front of us. We cried. That was Audrey, she wasn’t letting us forget. Years later my father would refer to this meal as The Death Duck Salad.

9

from a versified Old English life of St Guthlac of Crowland [Guthlac A, 266-279, 290-291; 349-355]

“In all our years watching your kind—how these spoiled twerps of the coastal elite puff themselves up with their own sense of accomplishment—we’ve never met anyone as shamelessly out of touch as you. You keep shouting about how you’re gonna force us out of here. Go on then. Or are you just God’s little bitch? And say you take this place, how will you survive? No one’s coming out here to feed you. Hunger and thirst will make you their enemy the moment you step out that door looking for food like a stupid fucking animal. Quit while you’re ahead. Give it up. You’re not gonna get any better advice than this. If you give a shit about living, go back to your friends.”

[The demons] kept flying out of their hiding places in the dark of night to check in on him, see if he was bored yet. They hoped he’d get homesick, miss his friends, head home. He wasn’t planning on it.

10

What is the one thing you wish was made of cast-iron but it is not?

a Bouncy Ball. - Aida Ramirez

Mountains. - Eli Petzold

a solution. - Gabriel Chalfin-Piney

Prompts (Key)

1. Why is the moth drawn to the light? Wrong answers only. (Maybe it’s an origin myth; maybe it’s a tragic soliloquy; maybe it’s the abstract for a Very Serious academic paper. If you choose this, you’re hereby forbidden from looking up the “actual” answer until you’ve finished.) - Aida

2. What died with the dragons? - Eli

3. Why is the moth drawn to the light? Wrong answers only. - Gabriel

4. How much space do you need? What is there with you once you arrive? - Aida

5. Below are the opening lines of The Wanderer, an Old English elegy that meditates on solitude & exile in the wake of catastrophe (the death of a dear friend, the violent disintegration of a community). The poem probes the deep pangs of isolation & dislocation, but it also offers an image of the ideal exile—their demeanor & their duties despite the suffering. Without looking up translations or OE dictionaries or any further information, “translate” these opening lines however you’d like. (FYI the letters ð and þ are both pronounced “th” - might help unlock some words, depending on how you choose to “translate.") - Gabriel

6. Write a map. - Aida

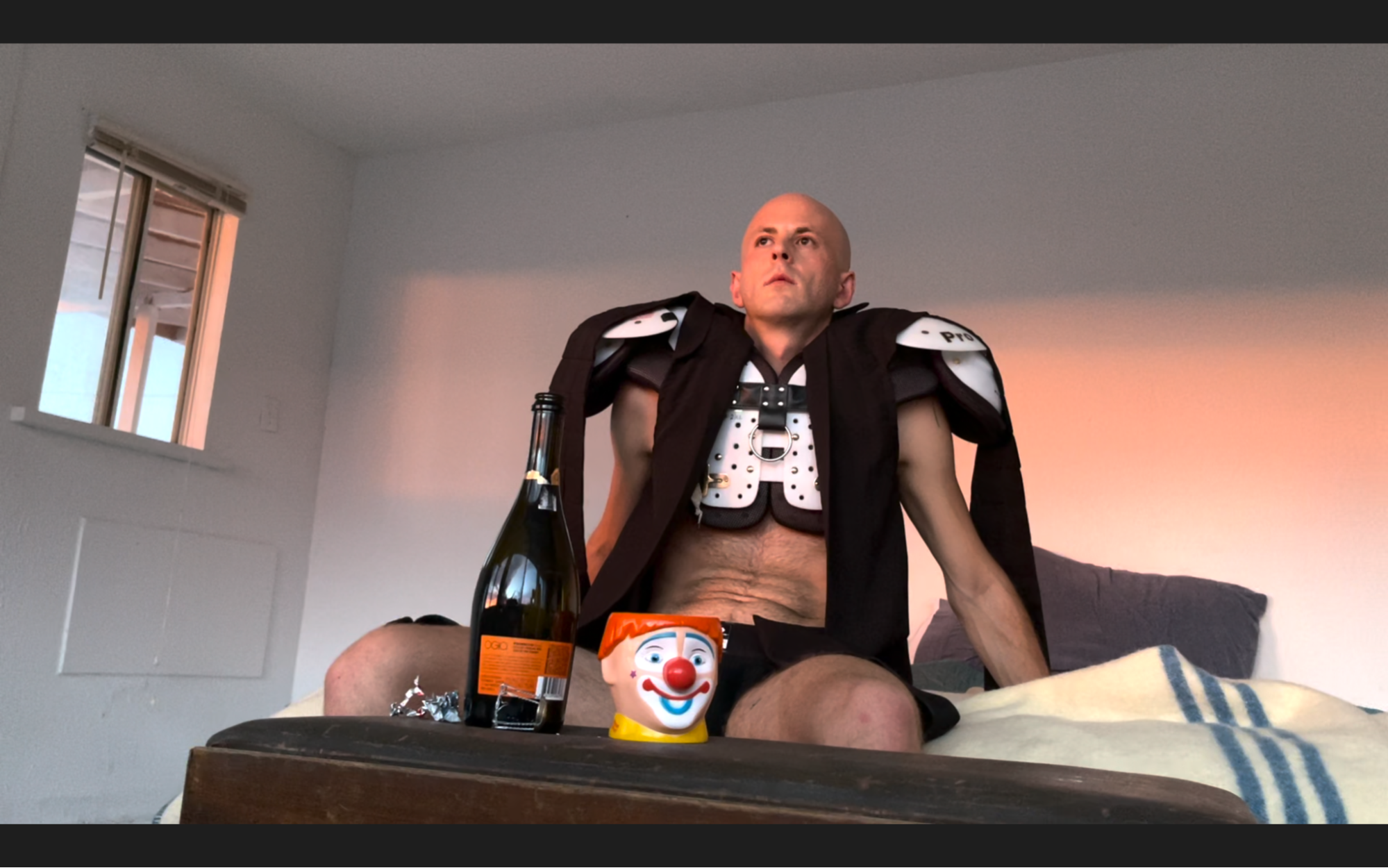

7. The characters Gabriel outlined (ie— Anchorite, Monster, Clown, etc.) have a certain degree of anti-hero-ness about them as they work (in either passive or active ways) against an established hero or establishment. In what ways do you imagine your own role being fulfilled as either a hero or anti-hero in your life? - Eli

8. The characters Gabriel outlined (ie— Anchorite, Monster, Clown, etc.) have a certain degree of anti-hero-ness about them as they work (in either passive or active ways) against an established hero or establishment. In what ways do you imagine your own role being fulfilled as either a hero or anti-hero in your life? - Gabriel

9. On a basis of “good” or “bad”: Is the Anchorite a “good” figure? Is religious seclusion a “good” performance of religion? - Eli